What's happening in Kensington: Week of Jan. 19, 2026

MLK Day cleanup, Lost Time comedy show and more.

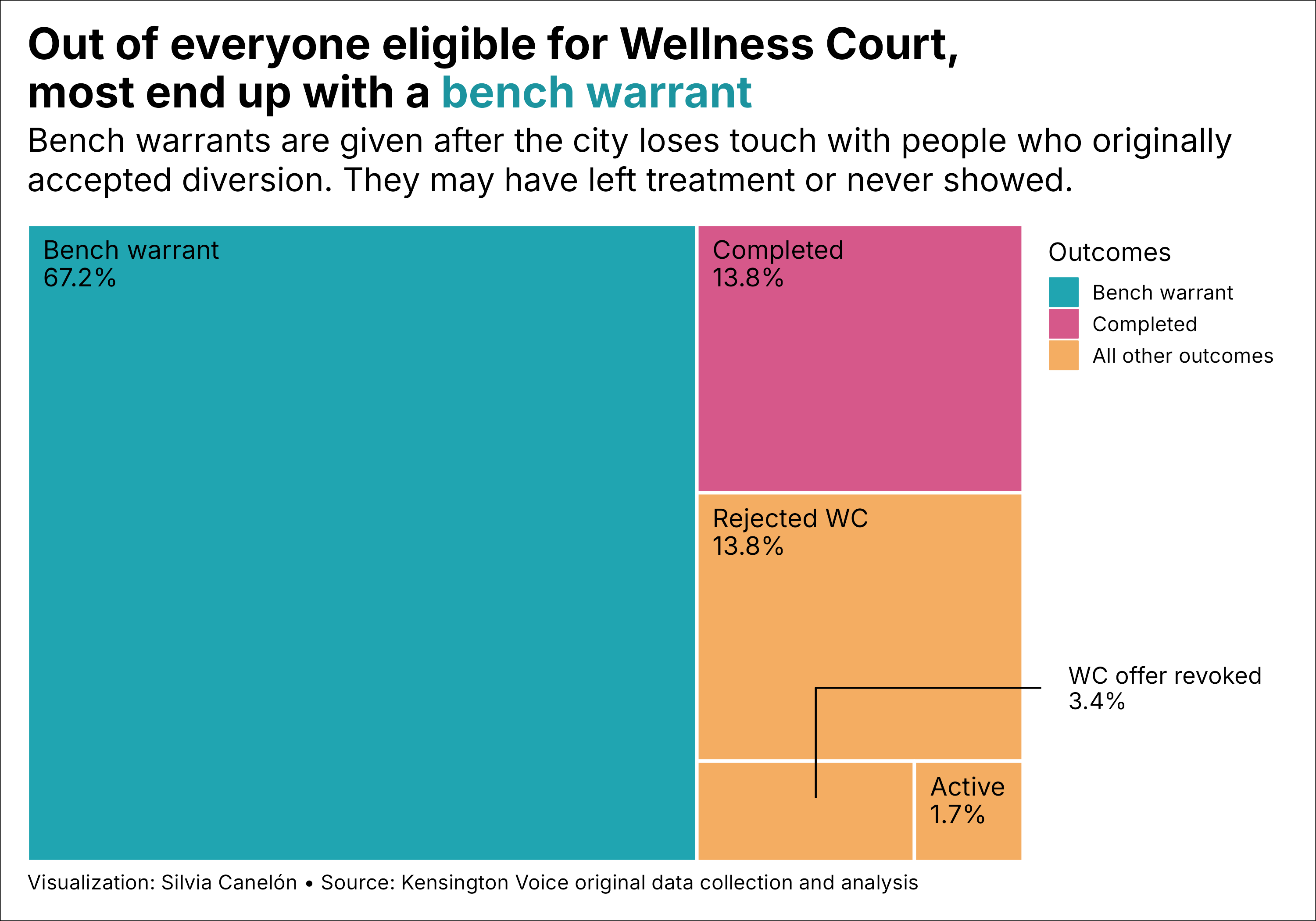

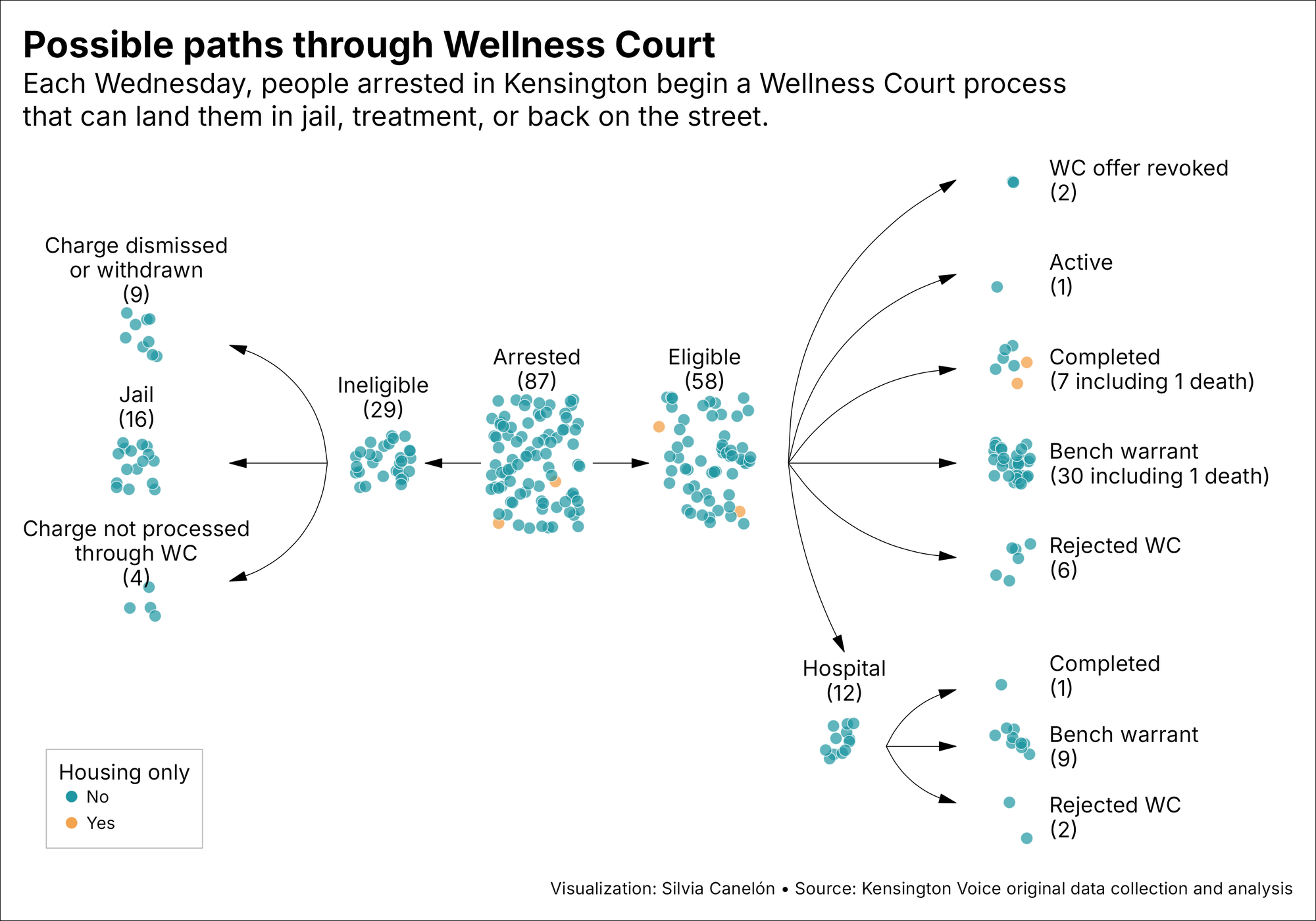

Kensington Voice collected and verified data on 87 people who were arrested during the first months of the program and tracked their journeys through the court. Most ended up with Wellness Court bench warrants after the city lost contact with them.

Dana looked exhausted when she appeared in court the same day she was arrested for trespassing on private property in April. She’d been living on the street for three years with a substance use disorder.

Alongside her in the courtroom were eight other people, some showing signs of withdrawal. One man was leaning over in his chair, his eyes closing. Another was shaking.

She was ordered to the front of the room to face Judge Henry Lewandowski.

“Being on the street is gonna end badly,” Lewandowski said, “but if you take advantage of what we’re offering you could save your own life. You could reconnect with your mother…this is your shot,” he added. “What’s it gonna take?”

“Housing,” she softly replied, adding that stable housing had previously helped her addiction recovery.

Lewandowski tried to convince her to accept an appointment for drug treatment that day.

“There’s no reason for you to be the next dead person,” he said.

He ordered her to return to court in two weeks. But Dana, 32, never returned, and the city’s attorney, who represented her, lost touch. Instead, she got a bench warrant. She was arrested again in October, and now has another court date scheduled for this week.

This is the Kensington Neighborhood Wellness Court — a fast-track court that targets unhoused people who use drugs by arresting them for low-level crimes and offering either diversion to drug treatment or a same-day trial. Mayor Cherelle Parker launched the initiative in January when she signed an executive order that allowed the Philadelphia Police Department to take people in Kensington into custody for minor offenses such as public intoxication or obstructing the highway, which previously incurred a ticket.

Legal experts, community leaders and outreach workers have publicly raised concerns about the ethics and effectiveness of the program. They criticize using police and the courts as points of entry to services for people who are in the throes of addiction and not voluntarily seeking help.

Kensington Voice collected and verified data on all of the 87 people who were arrested during the first four months of the program and tracked their journeys through the court until July 16.

Just eight of the 87 people who were arrested between January 22 and May 21 have been documented as completing the program, according to Kensington Voice’s findings. One of those eight is now dead.

“Are we focusing on punishing people or on creating more stability and care?” asked Kelsey León, a harm reduction advocate who works in Kensington with the Community Action Relief Project. “By beginning with arrest, you're creating further alienation and mistrust among people who you are ostensibly trying to reach.”

Andrew Pappas, managing director of pre-trials for the Defender Association of Philadelphia, who regularly observes Wellness Court, said that treatment “only works when people are ready to accept it and embrace it.”

Thirty-nine of the 58 people who were eligible for diversion — or 67% — ended up with Wellness Court bench warrants. This is a new kind of warrant issued to people who accept diversion but then don’t show up for court appointments and with whom the city loses contact. Another 16 people landed in jail on warrants for old charges.

Since January, at least two people who were arrested, Micheal Varra and Josue Mariani, subsequently died from presumed overdoses.

Varra’s family members say city officials told them he was found in an abandoned home in Kensington with drug paraphernalia about a month after his arrest in March.

He had accepted diversion and was directed toward outpatient appointments for the opioid use disorder medication buprenorphine, known by its brand name Suboxone. But he never showed up to his second appointment, according to Pappas.

“They'll give you that option, but you walk out them doors alone,” said Varra’s sister Alicia Penquite. “Does it bother me? Yeah, it bothers me ... I don't blame anybody else, he is his own person. I just wish things were different.”

The city marked Mariani as “successful” in May at his last Wellness Court hearing. What no one at the court knew, but a case manager for the Kensington Avenue outreach center Sunshine House recognized, was that he never stopped using drugs. He then overdosed in Kensington in August, according to Roz Pichardo, who runs the Sunshine House. Pichardo witnessed his death after giving him the overdose reversal medication Narcan.

“If this is what a success story looks like, it’s devastating,” Pichardo said.

In June, City Council approved a $3.7 million budget request from the Office of Public Safety, which oversees the court, to expand the program — despite the office sharing hardly any proof of success with the public and even after council pressed for data during an April budget hearing.

The city acknowledges it has taken on an immense challenge in trying to help a community of people who are unhoused and have complex medical needs, including mental and physical disabilities and substance use disorders.

“We knew this would be difficult — it didn't appear overnight and it won't be solved in that time frame — but we are committed to this work and continuously evolving our efforts to meet the needs we encounter as they arise,” an Office of Public Safety spokesperson wrote in a July statement to Kensington Voice.

In September, the city announced the hiring of the program’s first director, Eleni Belisonzi. Belisonzi previously led the Municipal Court Unit at the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office.

Solomon Furious Worlds, a staff attorney with the ACLU of Pennsylvania, fears the Parker administration will shift towards a “military, police-state type of strategy to criminalize extreme poverty.”

“We vehemently disagree with the city's approach in Kensington, of using the police and coerced treatment to try to alleviate what is a housing and health crisis,” Worlds said.

Wellness Court currently operates one day per week in Kensington, with police making arrests early on Wednesday mornings. They transport those arrested to the Kensington Wellness Support Center at B Street and Lehigh Avenue, where they’re evaluated by a nurse and multiple caseworkers. People deemed very sick are transported to the hospital and are later subpoenaed.

While held in custody, they are offered food, water, and clothing and can sign up to request housing assistance and public benefits. Some are funneled into case management services with other organizations including Merakey or Prevention Point.

Not everyone who’s arrested is eligible for diversion. Philadelphia public defenders are stationed at the support center to clear outstanding Philadelphia bench warrants for prior charges through a virtual courtroom. If a previous warrant can’t be lifted, an arrestee is taken to a Philly jail or picked up by police from another county (if their warrant is from outside the city).

Those eligible are transported to a courtroom inside the 24th Police District headquarters where they either accept or reject social services in front of Judge Lewandowski. Christian Colón, the city’s contracted attorney, represents them.

Accepting means the chance to go to court-mandated drug treatment. Over time, if they complete their court requirements, Colón can apply to erase their charges from their records.

Participants who reject diversion can accept a court fine without undergoing trial, which means the summary charge then stays on their record. They can also go to trial and plead not guilty. If they lose, they get a fine ranging from $198 to $498.

City officials have described the fast-track court program as a dignified way to connect some of Kensington’s estimated 800 unhoused people with services while also “restoring norms” in the neighborhood.

“We can do both,” said Adam Geer, chief public safety director. “We can treat those folks with dignity and decency and we can also continue to reinforce that the community deserves to be delivered from the trauma of living in an open air drug market.”

In March, Dominic, 46, was sitting on the sidewalk on Kensington Avenue, leaning against a storefront with a sweatshirt over his legs, when an officer arrested him. He didn’t have a wheelchair that day, which he needs for mobility, so an officer held him up as they walked to her car and hoisted him in.

He was taken to the support center, where he was held for several hours.

“They kept trying to pacify me in there by saying, ‘We're helping you.’ I said, ‘You want to help me? Release me,’” Dominic said.

Once in court, he rejected diversion and went to trial, pleading not guilty. He told Lewandowski it was “strange” to try to force people into treatment. Lewandowski ruled Dominic guilty and fined him $198.75 for court costs.

In April, weeks after his arrest, Dominic was in a wheelchair on the Avenue, still unhoused and using drugs. He described his Wellness Court experience as “traumatizing” and his arrest as unjust and confusing.

“I didn't do anything wrong,” he said.

Some observers in the courtroom, including Pappas, feel that the program disrupts peoples’ lives and rarely provides a lasting service connection or housing stability, which is considered vital to addiction recovery.

“They’re in a holding room and their movements are restricted for some number of hours,” Pappas said. “And that is stressful and traumatizing and they’re in pain” before they’re released without anywhere to go.

Dominic, who was born and raised in Kensington and has been unhoused and using drugs for the last six years, said getting to treatment and appointments when you’re on the streets is extremely difficult.

He doesn’t have the luxury of a deep sleep. He can’t keep his eyes closed for too long. He constantly worries about someone stealing his few belongings, all inside his backpack.

When he was arrested in March, he had recently completed an inpatient treatment program but wasn’t connected with housing or support services, he said. He was released from the inpatient program with medication, and told to set up a surgery he needs.

“Well, they knew I was homeless, so if you release me back out here in Kensington... my bag was stolen that same night with my meds,” Dominic said. “Every day, all day, I’m just trying to hold on to my stuff.”

Every week several people receive a Wellness Court bench warrant, either because they don’t show up for a court-mandated treatment appointment, or are a no-show in court. Their lawyer, Colón, then reports that he doesn’t know where they are. He acknowledges maintaining contact is difficult. Many arrestees don’t have cell phones.

Dan Sheehan, a case worker at Sunshine House, said Wellness Court isn't effectively calling on an existing network of service providers in Kensington who have relationships with many people living on the street. He thinks the city should invest more in outreach and case workers.

“It’s got to be a daily interaction for anything meaningful to happen here,” he said.

In its statement, the city acknowledged there are multiple “definitions of success” in their model. “It can and should be about accepting and completing treatment, which often takes more than one try,” the statement read.

The city added that the “personal care” from case workers “is vital to help people on their journey to recovery” and that it takes “multiple soft touch points to encourage people to come back."

It’s standard for people to need multiple engagements, but that doesn’t apply when there is an “extraordinary power differential, like between a police officer and an individual,” León said.

People also need a better understanding of the program’s conditions, Pappas said. Unlike a regular bench warrant, which can land someone in detainment indefinitely, a Wellness Court bench warrant is an open invitation to return to the system, get re-connected to services and have the warrant cleared, Pappas explained.

“I don’t know if people fully understand that,” he said.

Pappas thinks that misunderstanding could be a key reason people who miss Wellness Court usually never return.

“It pushes them into the shadows and makes them afraid of accessing treatment,” he said.

Kateri Andriole, who does mutual aid work with unhoused people in Kensington, was in Wellness Court taking notes almost every week from January to July and often talks to people who have been arrested for the program.

“It’s basically a bench warrant factory,” they said.

The program’s bench warrant rate is far higher than the rate in the Accelerated Misdemeanor Program (AMP), the city’s other diversion court. AMP is for people throughout Philadelphia who are charged with misdemeanors like possession and theft.

From August 2022 to July 2025, housed people who entered AMP had a bench warrant rate of 16%. Unhoused people had a bench warrant rate of 37%, according to the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office.

In AMP court, people are ordered to show up in court two weeks after their arrest, and if they show up under the influence, they get a later court date.

“In AMP, we don’t let you make a decision if you’re high, or if you’re actively detoxing, because you're not able to make a decision knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily, which is the standard to enter a plea or program,” said Caleb Arnold, supervisor for adult diversion in the District Attorney’s office.

When people show up to court and are not under the influence of drugs, they can be directly connected to services that day. People get to make decisions “in a better state than when they were arrested, a more ready state to think about, ‘What do I want to do with my criminal case and with treatment?’” Arnold said.

Lewandowski is the municipal court judge for both Wellness Court and the AMP program. He prides himself on his attempts to connect with people who stand in front of him.

He asks about their lives before addiction, their families, and their previous occupations. He asks what helped them get sober in the past. He says the court is there to help them, not punish.

Sometimes he uses harsh language, while also encouraging people to embrace the services offered.

“I’ve got a couple dead friends who said they were gonna go to treatment the next day,” he said. And “there aren’t better options out there. This is as good as it’s gonna get.”

But advocates worry that many people at Wellness Court are either so intoxicated or sick they likely can’t understand the situation or their choices. Andriole said people in court are often confused about their arrest.

Those in pain from withdrawal are apt to agree to diversion just to get out of the courtroom, said Andriole who has personally experienced opioid withdrawal. Wellness Court participants have been seen in the court room shaking, leaning over, or sliding down their chairs with their eyes closed.

James, a 35-year-old man who was arrested for obstructing the highway, was sleeping in the back of the courtroom on May 7. He was offered a chair during his hearing, and began to lean over as Lewandowski spoke.

Lewandowski asked, “You alright?” James said yes. The judge asked him if he felt like he was overdosing. Wilson said no. He was still leaning over in his chair. A police officer tapped him on the back to stir him.

James sat up. Then he slumped over again. The cop tapped him again. He woke up. He dozed off again. The cop tapped him again.

Lewandowski repeated his question about whether James was accepting treatment. He told Lewandowski he had been using drugs for 10 years. He said he has lacked “stability, accountability, and guidance.” He started leaning over again. The cop tapped him. He accepted residential drug treatment. Lewandowski gave him a court date for one week. He now has a Wellness Court bench warrant.

Legal experts say decisions about defendants’ cases should not be made when they’re impaired, and expressed this concern in a letter to the city before Wellness Court launched.

The city believes that “the program operates lawfully and conscientiously with the highest standard of legal ethics,” a spokesperson wrote in an October email, referencing the judge’s colloquy, which explains participants’ options once they get to court.

Marni Snyder, a Philadelphia-based criminal defense attorney who signed the letter and observed Wellness Court on its first day in January, witnessed one participant who was “slumped over," had “an unsteady gate,” and could not “focus their eyes” on the judge. She said law enforcement uses those terms to identify intoxication.

“It was ridiculous. That person should not have been in court,” Snyder said.

Lawyers are obligated to make sure that defendants are competent enough to make decisions, and that those choices are intentional and voluntary, Snyder said.

“We have the moral obligation to make sure that people don't walk out of a courthouse in the United States of America not having any idea of what just happened to them,” she said.

Wellness Court has had more success helping people clear their previous warrants than helping people complete addiction treatment and find housing.

During the first six months of the program, 60% of the 51 participants who entered with outstanding Philadelphia warrants had those warrants lifted, Pappas said.

Pappas sees the level of bench warrant clearing as a big victory because it prevents incarceration.

“Most of these people are suffering through substance use disorder, and so even spending a night in custody on State Road in forced withdrawal is potentially life threatening,” Pappas said.

Of the 87 people followed by Kensington Voice, the city has marked eight people as completions of the program. That includes:

Of the 87 people followed by Kensington Voice, the city has marked eight people as completions of the program. That includes:

Danielle, 44, is one of the city’s first success cases. She made it from living on the street in Kensington, to being arrested on a Wednesday morning, to the hospital, to an inpatient treatment program and then to Riverview Wellness Village, the city’s new long-term recovery housing complex.

She wasn’t present in Wellness Court until after she made it to Riverview. When she appeared in her first and only hearing, she admitted she didn’t know what Wellness Court was.

Lewandowski asked Danielle what was working for her. She said Riverview was nicer than any recovery housing she’d ever seen. But she said it was her wish to reconnect with her children and “wanting to be clean, that's what’s different this time.”

Like Danielle, Aziz’s success story is viewed by providers as a fluke, not having much to do with the court itself. It came about largely because of the above-and-beyond efforts of Diamond Stahl, a substance use navigator for Penn Medicine’s Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy who is city-contracted to work as a 'peer navigator’ for Wellness Court.

Aziz, 40, was arrested twice for Wellness Court. Both times he was sitting on the sidewalk. Following his second arrest he got a bench warrant after he didn’t appear for his court date and the city lost touch with him. Then he was back living on the street in Kensington. He fell asleep next to a fire he’d made to keep warm. When he woke up, he was leaning into the flames. He caught himself with his hand, burning it on plastic he’d used as fuel and was treated at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital.

That’s where he reconnected with Stahl, who is stationed at the support center on Wednesdays. She was only notified of Aziz’s location because he was on her caseload through Penn’s Warm-Line.

Over the course of his one-week hospital stay, Stahl visited him at least four times. She brought him clothes and spoke to his mother. She eventually helped Aziz find a recovery house, the very one Stahl stayed in while she was in recovery. She also got his rent paid for through a Penn program.

Stahl convinced Aziz to return to Wellness Court on May 21. He was nervous, he said, because he had a bench warrant and thought he’d be detained. But Stahl persuaded him he’d be able to show his progress and get his bench warrant lifted.

“I wasn't gonna go. She promised that I wasn't gonna get locked up,” Aziz said.

Stahl took Aziz to court. He showed up ready to share his story and Stahl advocated for him to the judge. Lewandowski lifted his warrant and his arrest record has been cleared.

He told Lewandowski about the fire and how he reconnected with Stahl.

“God let me feel the pain, so I can gain,” he said.

As of July, Aziz was doing well. He’s helped, he says, by the love he feels from his family – and his desire to return to their lives after years on the street.

He credits Stahl for motivating his recovery. “Some people are really putting in that footwork, they're out here in the rain, the sleet, the snow ... it's just in their heart.”

This story has been updated to reflect additional comments from the City of Philadelphia provided after publication and to clarify the relationship between Penn Medicine’s Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy and Wellness Court.

Have any questions, comments, or concerns about this story? Send an email to editors@kensingtonvoice.com. Or call/text the editors desk line at (215) 385-3115.

Free accountability journalism, community news, & local resources delivered weekly to your inbox.